Time budgeting my talent: Am I adding the most value to my farm?

Vital to the success of any farm business is that all of the tasks categorized as important to the farm but perceived as something a farmer doesn't do well eventually become part of a farmer's "Do Well" list.

Before I delve into the primary message I hope to convey in this article, let me suggest that an alternative title/question could be: Who serves as your farm’s CEO? The chosen title seems to allude to an opportunity for self-improvement while the alternate question could insinuate that something of importance might be missing from your business management function. Perhaps both questions might be relevant to your operation but the first is more inclusive – it pertains not only to the business’ owner(s) but anyone, at almost any level of management or line work. Ultimately, the owners of the business owe it to themselves to harvest as much benefit as possible from each and every employee of the business. A similar dynamic from a slightly different perspective is that the owners should attempt to harvest as much benefit as possible from each role in the business. I plan to discuss these parallel dynamics in one of my next articles.

For the purposes of this discussion, let’s focus our attention on you, the owner of a farm business. Are you adding the most value to your farm? The crazy thing about this question is that you are really the only person who can accurately (or at least honestly) provide the most relevant answer because you are the only person who knows how you are investing your time every day (24 hours), week (168 hours) or over the course of the year (8,760 hours).

Why this question is important

Let me quickly tell a story about one of your peers to help illustrate why I’m encouraging you to consider the question. I received a call a number of years ago from a farm partner who expressed concerns for herself as well as her husband and the multi-generational farm they were operating. She summarily described her perception of how they invested their time in managing the business as follows: “He milks, he feeds, he breeds cows, he plants, he harvests; I do the books. He is happy as a lark and I am too but the books aren’t so happy. I know we aren’t spending enough time in the office.” I asked her what “office time” meant to her, to which she indicated meant higher level thinking and all of the big picture and planning “stuff.” This story should sound familiar to every one of us – yes, I’m including myself because I, too find it very easy to get caught in the weeds of everyday business “stuff.” In reality, this discussion is about self-improvement and ultimately, is another component of continuous improvement which you’ve seen me write about many times previously.

How can you go about answering the question

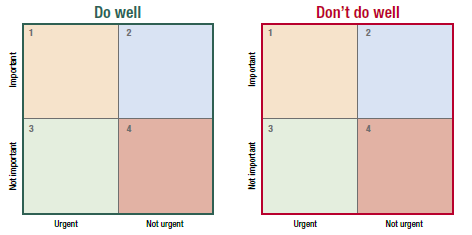

I often speak with my clients about maintaining a skills and talents inventory of both owners and employees to optimize the efficiency of their staffs. But for this conversation, I’m going to ask that you do something a little different. Take two sheets of paper and block them both as depicted in Figure 1 below. On the first sheet, write “Tasks/Functions I Do Well” and title the second sheet “Tasks/Functions I Don’t Do Well.”

On the first sheet (Do Well), list all of the various tasks and functions you perform as an owner/manager of your farm on a regular basis, placing each item in the appropriate box (1-Important/Urgent; 2-Important/Not Urgent; 3-Not Important/Urgent; 4-Not Important/Not Urgent). Items appearing on this list should only include tasks and functions which are being performed by you in a satisfactory or above-satisfactory manner. Important tasks and functions are things that contribute directly to your long-term mission and goals. Urgency should be thought of as the sense of immediacy in which the task or responsibility must be performed (today vs. over the next month). Now take out the second sheet (Don’t Do Well) and list in the appropriate boxes relating to their importance and degree of urgency, the tasks and functions that are currently being performed in a less-than-satisfactory manner or are areas in which you specifically want to improve.

Once you have filled in the squares on both sheets, lay them side-by-side and review both with a critical eye. Think about the tasks and functions on the Do Well list; do they happen to be items that you also happen to enjoy doing? Take another minute to look at the Don’t Do Well list; do you happen to dread any of those tasks and functions? Sometimes it’s just plain human nature for the owner of a business to immerse themselves in activities that they enjoy doing and avoiding those that aren’t quite as pleasant – it’s not always a matter of skills and abilities but rather more of a matter of preference and comfort. This dynamic is what I meant earlier when I referred to “getting caught in the weeds.” On many farms, the most common functions listed in the Important/Not Urgent section of the Don’t Do Well sheet would include business planning, risk management, succession planning, directing human resource management, etc. Coincidently, these functions happen to be among the primary responsibilities of the company CEO – which is why I offered the alternative title/question: Who serves as your farm’s CEO?

In any case however, it is vitally important for the success of any business that all of the items that have been categorized as important on Don’t Do Well sheet eventually become part of the Do Well list, especially those in the Important/Not Urgent category.

How to solve the problem

We should now consider the problem of “time.” Many readers will likely express frustration with my idealistic perspective on investing more “time” and energy in the Don’t Do Well items. They would say that they don’t have any more time, that is unless they only sleep seven hours per week. This dynamic is the essence of the title of this discussion: Am I adding the most value to my farm? If there are any important tasks and functions on the “Don’t Do Well sheet, especially in the Important/Not Urgent category, then the answer most definitely is “NO.” If it can be fairly judged that you are not adding the greatest value possible to your operation, then you owe it to yourself and the business to take intentional steps to improve. Here are a few examples of steps you can take in the improvement process:

DELEGATE Delegation is without question one of the most powerful but most elusive management skills. Anyone who makes a serious effort to carve out time to maximize their management value must discipline themselves to become an effective delegator.

TRAIN Corporate America invests billions of dollars every year in education and development training at every level of management. Identify a key management skill in which you want/need greater proficiency and seek out related training opportunities. Local/regional trade associations, online providers, local career centers and universities are all potential sources for professional development training.

LEAN ON ADVISORS Start a conversation with your most trusted business consultant or advisor and ask her/him for their feedback, input and suggestions.

BUILD BETTER TIME DISCIPLINE Begin by setting aside 15 minutes per week, every week to be invested solely toward one of your identified improvement areas.

Select a time that coincides with another part of your routine (e.g. extending your morning mealtime on the day which typically has fewer other scheduled activities) to make it easier to commit to the time slot each and every week. Over time, extend the allotted time for this and other improvement functions.

There is one more dimension to this conversation that I haven’t addressed. No one person can be expert in every management function, which is the reason farm businesses have co-owners, partners, employees and advisors. Your mission and goals are more likely to be accomplished if you are vigilant in insuring that you are not only adding the most value to the business, but also the entire team. Abraham Lincoln is credited with having said “Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe.” I encourage you to take some time to sharpen your axe.